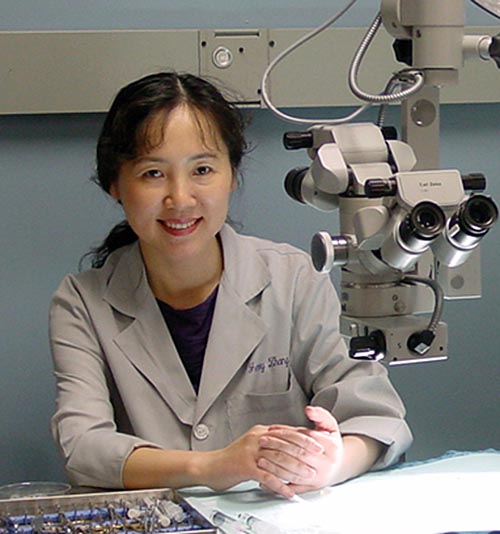

Meet the Faculty: Zheng Jenny Zhang

Zheng Jenny Zhang is a Research Professor of Surgery in the Division of Organ Transplantation at the Feinberg School of Medicine. In this interview, Zhang discusses her research focuses, her collaborations with nanotechnology experts at SQI, and her role as director of the Microsurgery and Preclinical Research Core at Feinberg’s Comprehensive Transplant Center.

How would you explain your research to a non-scientist?

I’ll start by saying that I’m a trained transplant surgeon, and that I’ve been doing research for the last 20 years. All my research addresses some critical questions and challenges we see in organ transplantation, which includes transplant injuries and also the immune response that recipients mount against transplanted organs — called rejection. If there’s no drug, the transplanted organ will fail very quickly, so we’re trying to understand how that happens and develop strategies to minimize rejection.

There are a lot of drugs for immune suppression that are already used in clinical practice to keep transplanted organs alive, but they are not optimal. There are side effects and the patients need to take these drugs their entire lives because the immunosuppressants are not specifically targeted to cells and they can harm the organ. So, my research is to identify key molecular mechanisms underlying the rejection process, and by doing that we want to develop strategies to target specific, key molecules that can mitigate rejection.

Why did you choose the research track over the clinical track?

I passed the board exam for transplant surgery but I decided to stay on the research side for multiple reasons, including family reasons. Mostly, I’ve found that research is fascinating, and I can really use all these tools to see if there are better ways to treat patients so they don’t need to take as much immunosuppression.

What attracted you to organ transplantation as a specialty?

To be honest, it was assigned to me because we had a very different system back then in China. We could list three choices and my first pick was pathology. I liked pathology because, in my university, if you did pathology, it was half clinical practice and half teaching, and I really liked teaching.

Organ transplantation was my second choice and we had a large transplantation institute at my university (Tongji Medical University) where they were doing a lot of research. I found it very intriguing, and the field in general is unlike others in medicine because patients can have a transplant and come back to life in a very dramatic way. You can have a very sick patient, but after an organ transplant they can be relatively healthy and have a good quality of life.

How did you get connected with some of the nanotechnology-based researchers at SQI, like Sam Stupp and Evan Scott, and what are you working on with each of them?

I was working on a project where we identified a protein that affected the innate immune response and was very critical for transplant rejection. We published a few papers on this topic, and I was trying to find a way to target this particular protein. I bought small chemical inhibitors from a company but they weren’t very effective in our mouse transplant models even though they had been effective in cell cultures. Then I came across one of Sam’s seminars and I thought his nanofibers could really make a difference in how we formulate a treatment, because we can deliver it locally with minimal toxicity.

The whole Comprehensive Transplant Center was very interested in working with a nanotechnology institute (SQI) because we have a common goal to identify new therapies, so we had a group meeting with Sam, Shad Thaxton, and Evan Scott and exchanged research. We learned the differences between all the nanoparticles they are using, which each have their own advantages. Now, we’re trying all these methods to mitigate transplant rejection or ischemia-reperfusion injury, which occurs after blood flow is restored in a transplanted organ and can exacerbate rejection.

Our Department of Defense grant is looking at how we can use the Stupp group’s nanofibers to coat regulatory T cells and allow them to preferentially home to a transplanted organ and accumulate there to more efficiently modulate the immune response.

My NIH grant is using Evan Scott’s nanoparticles because they published a paper showing they could target specific immune cells, macrophages, with their delivery system. In that way, we can target intracellular proteins that affect the function of cells.

You are the founding director of the Microsurgery and Preclinical Research Core at the Comprehensive Transplant Center. Can you tell me a bit more about what that Core offers and your role there?

This Core offers mouse surgical models that require a lot of specialized training to perform. Since I was a surgeon and I’ve been doing research in animal models for a very long time, I’ve developed several transplant models. We thought that we could offer our expertise to help investigators that have great ideas but do not have in vivo animal models to test them.

Initially, we were doing transplant surgery but then we expanded to other models, like inducing ischemia-reperfusion injury, and then in the last few years we’ve added a service to provide a diagnostic blood test for before and after surgeries. We acquired two bioanalyzers that allow us to take a few drops of blood to test liver function, kidney function, and about 10 other tests. This gives PIs easy access to a lot of tests in an effective way.

What are your main hobbies outside of research?

I’m with a singing group and we practice almost every weekend. We make videos and participate in community shows and performances occasionally, but mainly we just enjoy singing and practicing together.

I’ve been with Dong Fang Performing Arts, which has a larger choir, for more than 10 years. But right now, my favorite is singing with a smaller ensemble named Qiuyun Ensemble — it’s really fun.

When you look back at your career so far, what are you most proud of?

There are a lot of things that I’m very proud of, and I also have a lot of regrets [laughs]. But in terms of my research, I’ve developed a couple of transplant models that have been used by many researchers in the transplant field. By running the Core, I have been able to help a lot of PIs across different specialties and different academic institutions, while continuing my own research looking at mechanisms of transplant rejection and how to identify targets for treatment. I’ve published a number of papers in peer reviewed journals.

I have been a treasurer for the International Society for Experimental Microsurgery (ISEM) and this year was elected as the president for that society, so in two years I will be the president of ISEM. I also received the Sun Lee Award from ISEM in 2021 for outstanding research in experimental microsurgery.

I’m just a regular person, but I’ve tried to make a difference by doing research and running a Core.